Harmonizing with the Temiar: An Exploration of British Malaya Radio History and Indigenous Music

By Abdul Azeem Shah Bin Akbar Shah

The history of radio in Malaya traces back to 1921 when A.L. Birch, an electrical engineer working for the Johor Government, introduced the first radio set to the region. This introduction led to the founding of the Johore Wireless Association, pioneering radio broadcasts through 300-meter waves. Subsequently, similar associations were established in Penang and Kuala Lumpur. In 1930, Sir Earl of the Singapore Port Authority introduced shortwave broadcasts, occurring every two weeks on Sundays or Wednesdays. The Malayan Wireless Association, broadcasting from Bukit Petaling in Kuala Lumpur, also adopted this practice, utilizing 325-meter waves. Notably, in 1937, Sir Shenton Thomas inaugurated the Studio of Broadcasting Corporation of Malaya, along with its transmitter at Caldecott Hill in Singapore.

The Empire Service of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) was introduced in December 1932, broadening the spectrum of programs available to local residents. The British government granted a monopoly license to the newly established British Malaya Broadcasting Corporation (BMBC) in the preceding year. This marked the inception of a significant commercial radio station in Singapore, with initial test transmissions commencing in January 1937. BMBC undertook a substantial endeavor to serve the extensive population of Singapore and southern Johor by constructing new studios and transmitting and receiving stations at Caldecott Hill. The radio service, inaugurated on March 1, 1937, employed medium wave bands, making broadcasts accessible to a broader audience with more affordable medium wave radio sets. Additionally, in 1938, shortwave transmissions were introduced to extend the broadcaster's reach to the entirety of Malaya.

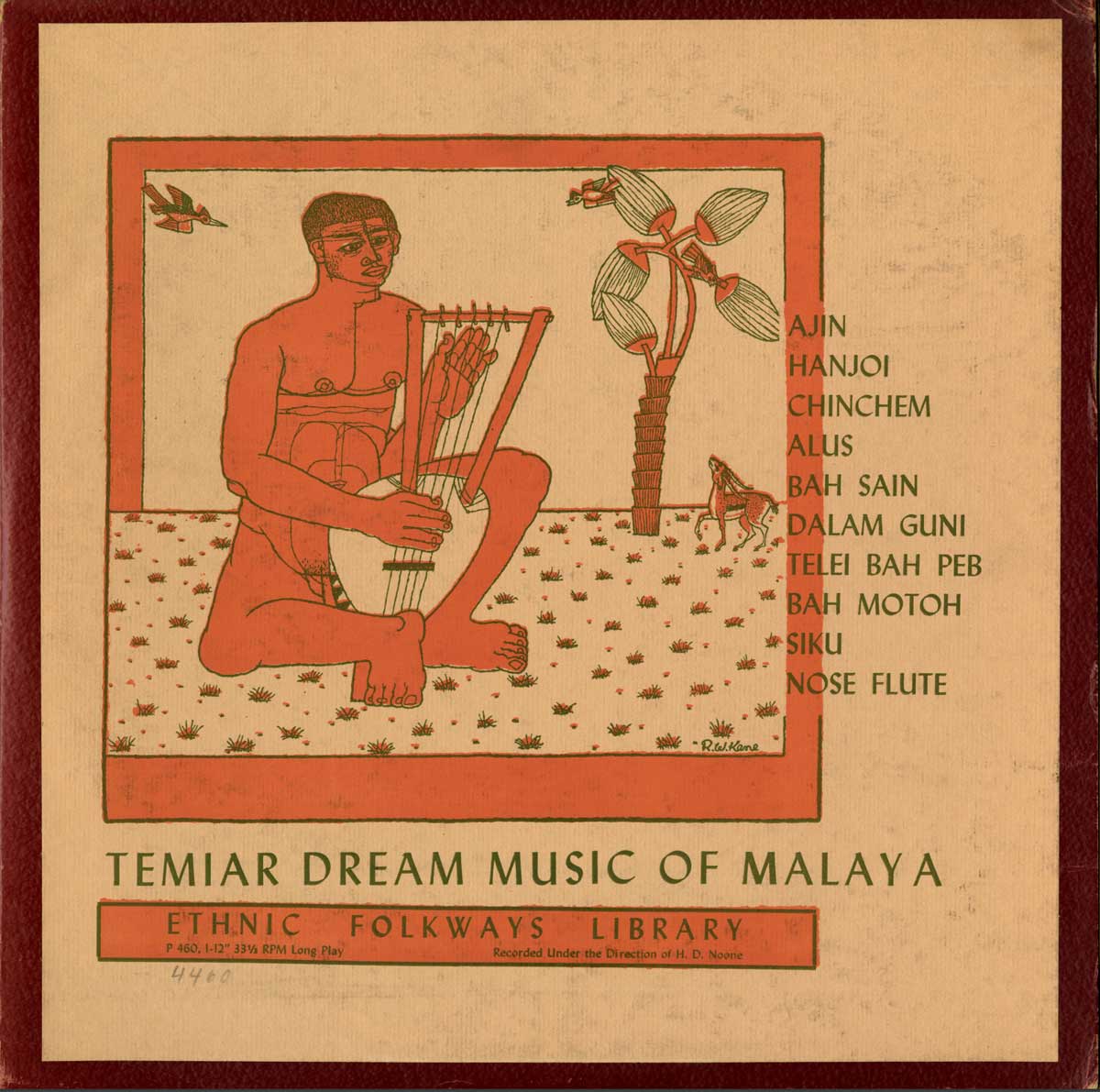

During a mission in December 1941 to record military activities and performances across the Malay Peninsula, the Malaya Broadcasting Corporation utilized an experimental mobile recording unit. Interrupted by the outbreak of war with Japan, the expedition resulted in valuable recordings of the "dream" music of the Ple-Temiar aborigines, who reside in the central mountain range of Malaya. The idea of recording Temiar music was conceived about three months prior to the 1941 expedition during a visit to the Perak jungle by D.H. Noone, Field Ethnographer, F.M.S. Museums, and Protector of the Aborigines, Perak. Noone, who had dedicated years to studying the unique culture of the Temiar, was deeply impressed by the pivotal role of music and dance in their lives and the profound connection between these artistic forms and their shamanistic spiritual beliefs. Recognizing the significance of Temiar music and its educational value, the producer proposed the idea to the Chairman of the Malaya Broadcasting Corporation, Mr. Eric Davis, who wholeheartedly supported the initiative. Upon gaining approval, the mobile recording equipment was prepared, and plans were made for an extended tour of the Malay Peninsula.

The expedition included visits to divisional headquarters and various army units in Kedah State, passing through Upper Perak, a region where Noone was actively engaged under the orders of Malaya Command which provided an opportunity to record Temiar music. Noone had two months to arrange for the gathering of prominent Temiar singers, and their dedication was evident as some traveled over a hundred miles across treacherous jungle-covered mountains to reach the rendezvous.

Recording Temiar music presented various challenges, for instance, persuading the Temiar to sing on command. Typically, the Temiar only sang and danced when summoning their spirit guides, and these activities were inseparable. To maintain technical accuracy, it was crucial that the performers sang without dancing. However, D.H. Noone possessed the influence and rapport to persuade the Temiar to sing and dance in isolation from one another, making the recording possible. The value of Temiar music recordings goes beyond cultural preservation. These recordings offer a direct glimpse into the "dream culture" of the Ple-Temiar, a group of Malayan aborigines living in the remote jungle-covered mountains of the Malayan main range.

The Temiar way of life is characterized by small communities, long-house living, shifting cultivation, and subsistence activities such as hunting with blowpipes, fishing, and collecting jungle produce, all organized along cooperative lines. Beyond the material aspects of their existence, the Temiar maintain a deep belief in a spiritual world. This belief not only sustains their interest in life but also inspires their motivation in cooperative endeavors. Their unique interpretation of reality transforms the mundane into the extraordinary. While previously dismissed as a form of animism, the Temiar religion is revealed to be far more intricate and profound.

However, the Temiar people, part of Malaysia's indigenous communities, face a myriad of challenges threatening their unique cultural heritage and well-being. Their traditional lifestyle, deeply rooted in the rainforest, confronts encroachment from industries like logging and mining, leading to forced displacement, economic loss, and cultural dislocation. Land rights remain a pivotal issue, with slow implementation of indigenous rights leaving the Temiar vulnerable to corporate land grabs. Commercial deforestation not only deprives them of essential resources but also disrupts their cultural and spiritual ties to the land, exacerbating issues like biodiversity loss and climate change. Social stigma and discrimination restrict their access to education, employment, and social services, while the encroachment of modernity poses the risk of eroding their traditional knowledge and customs.

The preservation of the Temiar community's well-being and cultural legacy necessitates a concerted, collaborative effort involving the Malaysian government, civil society organizations, and the international community. Essential focus should center on safeguarding land rights, preserving cultural heritage, and enhancing socioeconomic conditions. Recognizing and respecting indigenous rights isn't merely an issue of justice; it's pivotal for Malaysia's diverse cultural heritage and its sustainable future. Urgently addressing these concerns is vital in upholding principles of equity, and cultural preservation for the Temiar people and other indigenous communities facing similar challenges.

Simultaneously, the recordings of Temiar dream music, captured under challenging circumstances, stand as invaluable artifacts for anthropology and musicology. They unveil the intricacies of a culture deeply intertwined with spiritual beliefs, where music serves as a vibrant reflection of their spiritual world. These recordings provide a unique insight into the historical development of the Temiar culture and offer a priceless repository for future exploration and study. As the world rapidly changes, these recordings play an indispensable role in preserving the heritage of a people for whom inspiration remains a vivid and integral aspect of their daily lives.

Understanding Temiar music enriches our understanding of the elements that have molded the Temiar culture over history.

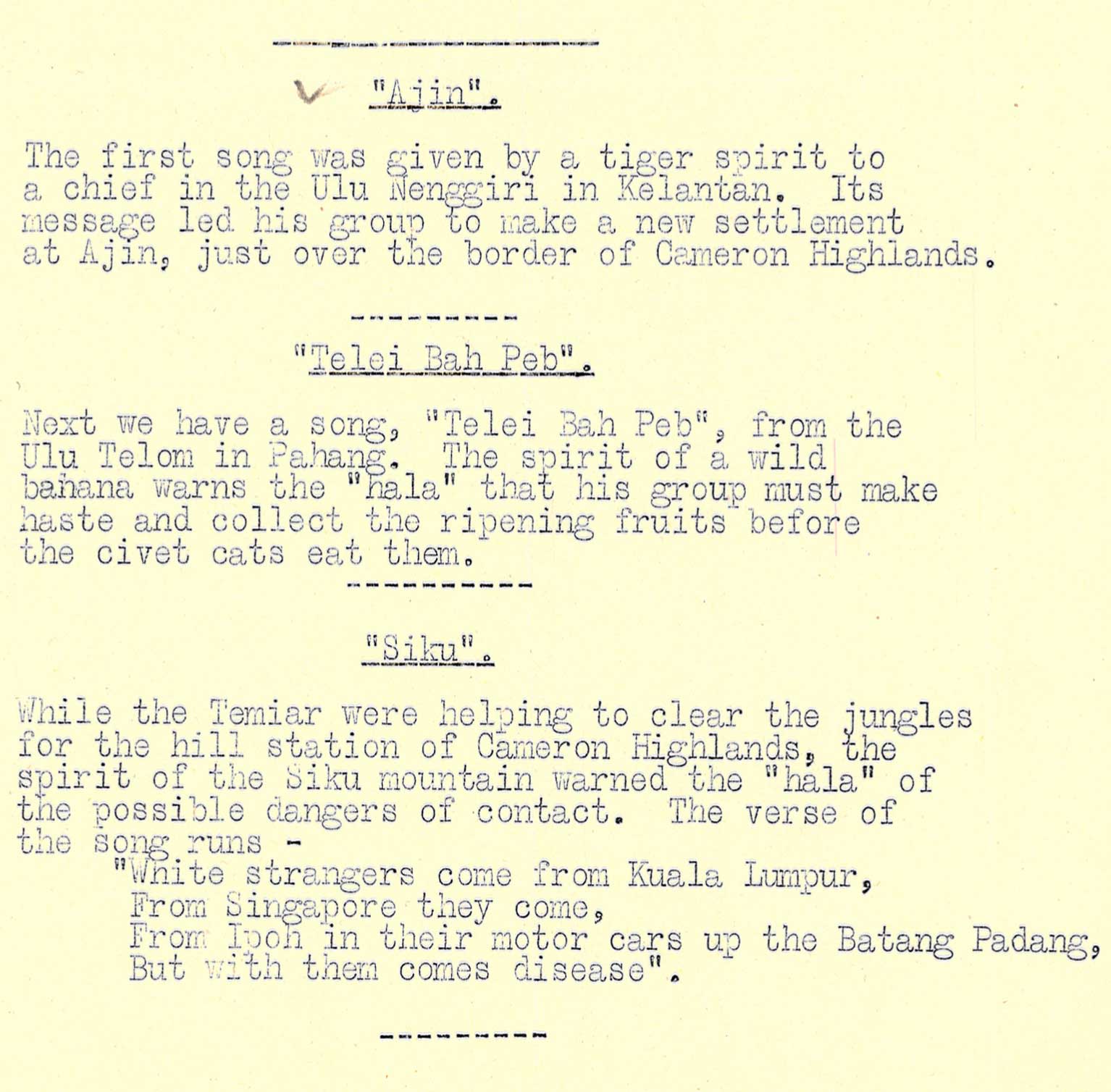

Telei Bah Peb (Spirit of the Wild Banana Fruit)

Song from the Ulu Telem in Pahang. The spirit of a wild banana warns the 'hala' [shaman] that his group must make haste and collect the ripening fruits before the civet cats eat them

Siku (Spirit of Siku Mountain)

While the Temiar were helping to clear the jungles for the hill station of the Cameron Highlands, the Spirit of the Siku mountain warned the 'hala' [shaman] of the possible dangers of contact. The verse of the song runs - " White strangers come from Kuala Lumpur, From Singapore they come, From Ipoh in their motor cars up the Batang Padang, But with them comes disease"

Song was given by a tiger spirit to a chief in Ulu Nenggiri in Kelantan. Its message led his group to make a new settlement at Ajin, just over the border of Cameron Highlands

Dalam Guni (Spirit of the Hills)

Dalam guni, or inside the sack, conveys the message when the spirit of the hills told a 'hala' [shaman] in the Ulu Perak that once upon a time a sack of rice was buried in the ground, and a very rich plantation resulted

In the Ulu Nenggiri in Kelantan dreamed this song when he and his group were felling a new clearing for cultivation. The spirit of the tiger gave him a song because - "we tigers here are amazed and not a little frightened of the power of you fellows - you even fell the biggest trees. We leave you in peace and give you this song as a token"

Title is a play upon words based on the disappearing form of a man who has dived into a pool to catch fish. His body gets smaller until it disappears. This is a variation on the higher the fewer.

Mixed chorus (male and female), drums and idiophone.