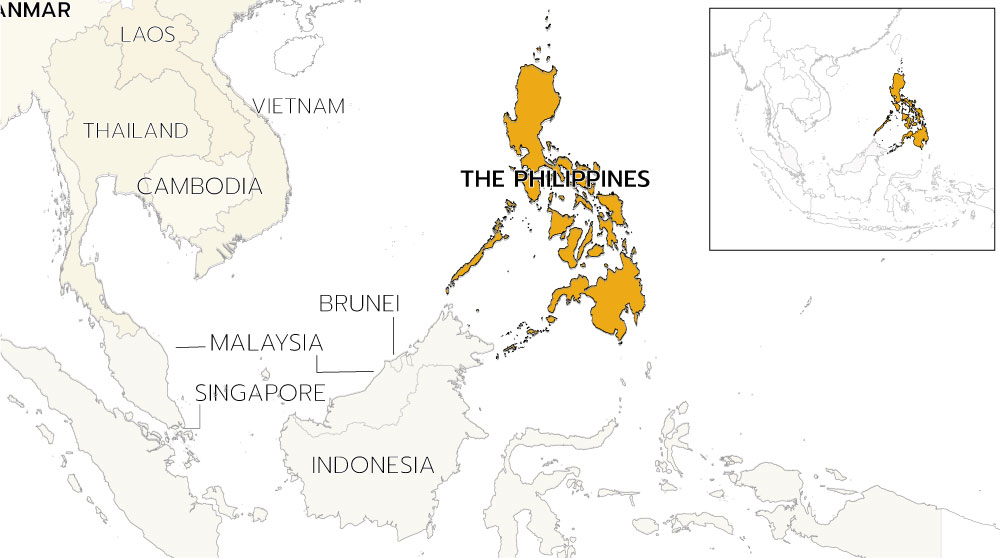

Philippines

- 1922— Three small stations owned and operated by an electrical supply company went on the air in Manila and adjoining Pasay City. Used mainly for demonstration purposes, the stations were operative for about two years before they were replaced by the 100-w. KZKZ station.

- 1931 —The Radio Control Law was passed, enabling the secretary of commerce and industry to watch over the medium. A regulatory body, Radio Control Board, was a result of the. law and functioned until martial law in 1972.

- 1942 All radio stations were shut down except for KZRH which was renamed PIAM and used as the Japanese broadcast outlet.

- 2 July 1946 Congress enacted Commonwealth Act 729 giving the President a four year right to grant

- licenses.

The BBC in the Philippines (by Elizabeth L. Enriquez)

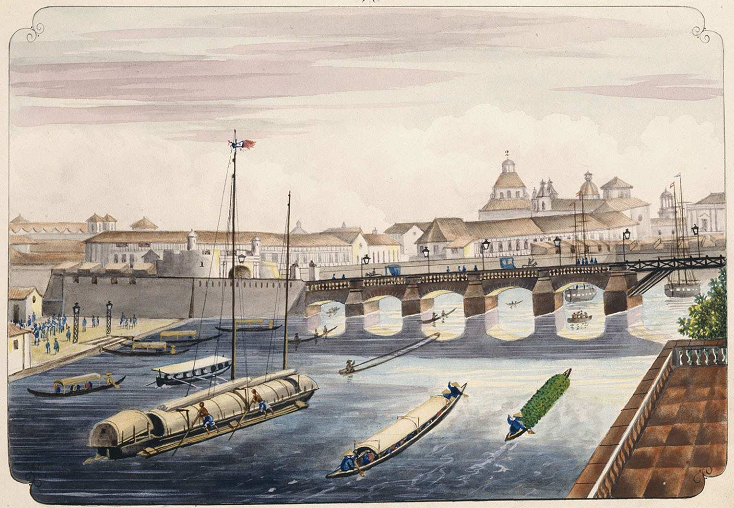

The BBC did not have a strong presence in the Philippines during the first few decades of the 20th century when the technology of radio broadcasting quickly developed around the world. It understandably targeted the populations of the British Empire, of which the Philippines was not a part. As a United States colony at the time, Filipinos were more tuned in to American radio, which was influential in the development of broadcasting in the archipelago. Nevertheless, with the advancement of shortwave radio in the 1930s, the BBC as well as other broadcast stations around the world were heard in Manila.

However, when World War 2 erupted, the signal of the BBC became one of the reliable sources of war information in the Philippines. Both the Allies, international military coalition to which both Britain and the United States belonged, and the Axis powers, the other international military group that started the war, which counted Germany and Japan among its collaborators, engaged in intense propaganda on all existing media platforms at the time – print, cinema, and radio broadcasting. Under Japanese occupation, Filipinos were forbidden to listen not only to American shortwave radio but also to the BBC and radio broadcasts from the Allied countries.

But not a few persisted in listening to forbidden radio signals and risked their lives by the mere possession of shortwave radio. Perhaps more significant was the growing maturity and intelligence of audiences in the face of suppression. They listened to the newscasts on the American military station KGEI and on the BBC. Many Filipinos hid their radio sets and avoided registration, so that less than half of the estimated 80,000 sets—which another estimate put at 100,000—were registered.(1) This implies that as many as 40,000 to 50,000 sets may have tuned in to KGEI and the BBC in the Philippines during the war, not counting the guerilla groups in the rural areas. Several clandestinely transcribed BBC and KGEI broadcasts for underground circulation. (2)

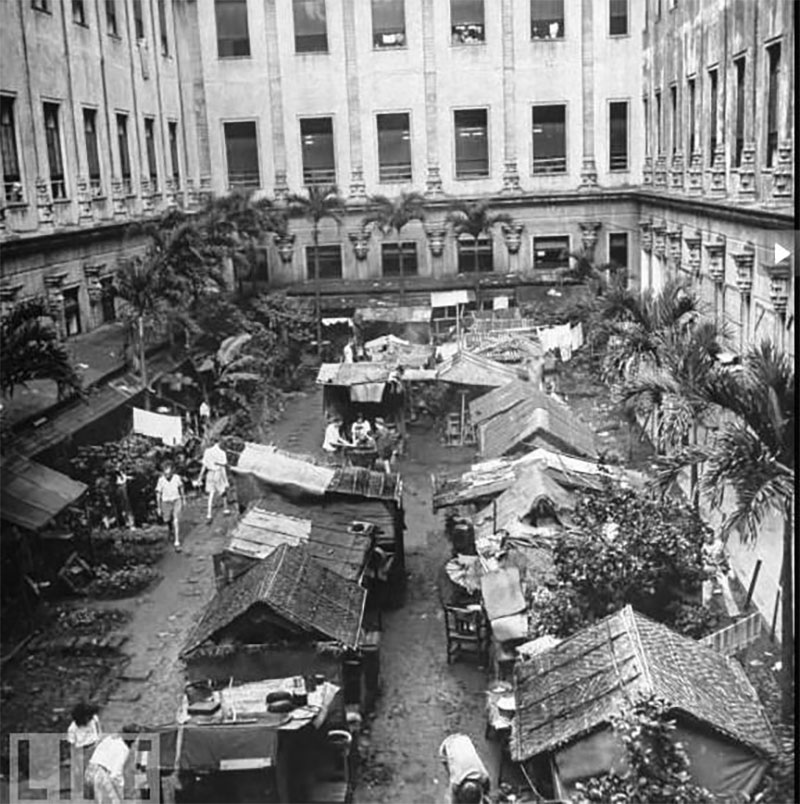

At the Santo Tomas Internment Camp, or STIC, in Manila where about 4,000 civilian Americans and other foreigners were kept during the war, there were shortwave radio receivers in the camp hidden by some internees who regularly listened to KGEI, the BBC, and other overseas shortwave stations. The camp’s clandestine receivers received Radio Chungking at night, when it came in strong, BBC early in the morning, Radio New Delhi at midnight, and KGEI at 7 o’clock in the morning. (3)

People listened to everything their sets would receive. However, they were not uncritical listeners. Former STIC internee Myron Wiener reported after the war that KGEI was the American station best received and most listened to because of the good reception, but BBC programs were preferred for its “higher quality.” He said, the news of the BBC was understood to be “more factual, more detailed, more precise, more meaningful; statistics are given; less bombastic and dramatic and never overstated, (with) fewer adjectives (and) superlatives, less dramatized; the British get emphasis by understatement.” Wiener, an American, commented that the BBC sounded like it had a definite propaganda policy, while the Voice of America propaganda seemed to have no policy, and the points tried to be made were clumsy.”4

In 1945, following the end of the war, Filipinos once again favored the American brand of broadcasting, which was commercial in design, but listening to the BBC also became a habit for some. ***

___

(1) 1940 Upped Philippine Radio 200 Percent, The American Chamber of Commerce Journal, January 1941, 24.

(2) Ricardo T. Jose, “Underground Writing During the Japanese Occupation: Resistance and Humanity,” in Panahon ng Hapon: Sining sa Digmaan, Digmaan sa Sining, ed. Gina V. Barte (Manila: Cultural Center of the Philippines, 1992), 62.

(3)A.V.H. Hartendorp, The Japanese Occupation of the Philippines, Vol. I, p. 470, Manila: Bookmark, 1967.

Read More

Malaysia

Indonesia

Singapore

Myanmar

Hong Kong

Vietnam

Thailand

Cambodia

The Philippines

Brunei

Laos

Timor-Leste