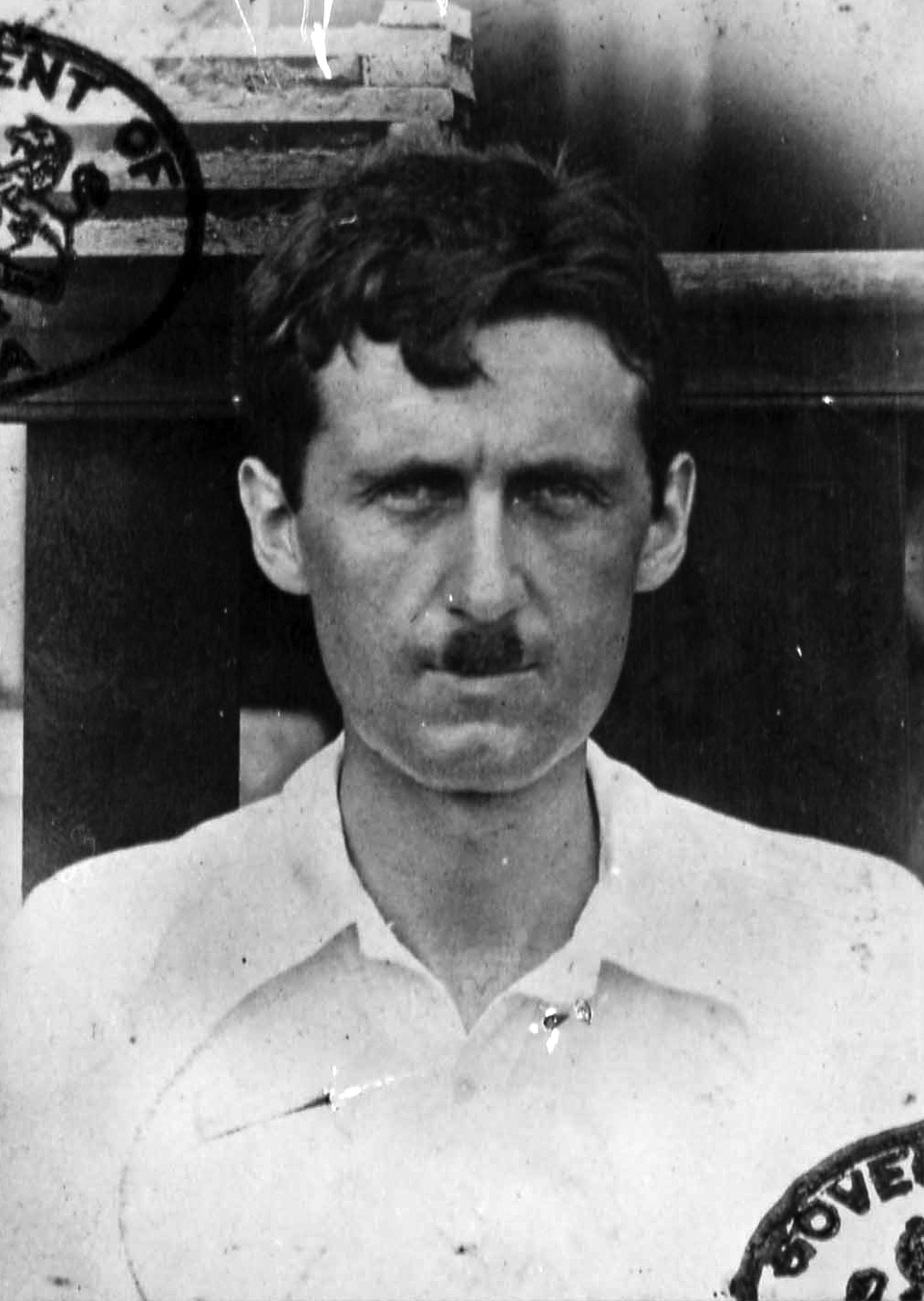

George Orwell

In a lengthy but entirely fascinating debate in the House of Commons about the role of the BBC in the Cold War, George Orwell is caricatured as an example for what not to say in BBC broadcasts to the Far Eastern Service:

The contrasts between the Far Eastern section of the B.B.C, and the activities of Radio Malaya and Radio Hong Kong are very great indeed. We must obviously be careful lest anything which we say on the air is such as in any way to help the Communists in their plans. If it were possible for them to make direct quotations from any of our broadcasts, whether in the Far Eastern service or the Home service, but particularly in the Far Eastern service, we should obviously be broadcasting material which was not appropriate.

I have in my hand the script of a Third Programme broadcast. Many of these are—

Mr. Gordon-Walker:

May I ask the hon. and gallant Member whether this went out over Radio Ceylon?

Major Tufton Beamish:

I dare say that the right hon. Gentleman does not like the line which I am taking, but these are important matters. My answer to his question is that, so far as I know, it did not actually go out over Radio Ceylon. It seems that the right hon. Gentleman Toggle showing location ofColumn 2612intends to ask whether I am in order. Perhaps he will let me take orders from the Chair and permit me to develop my argument. Anything which we say about the Far East, and that is what we are discussing, can have a damaging effect if it can be quoted back at us. The main question which I am putting is whether we would approve this Agreement if the money involved in it is to be wasted because that station is not going to carry out the propaganda which we want it to do.

This is an example of the sort of thing said recently on the air by the B.B.C, and, for all that I know, repeated in the Far Eastern section. It is an example of the sort of thing which, I feel, should not be sent out on the air at this juncture. It is only one brief example; an extract from an amusing story called "Shooting an Elephant," by George Orwell. I will read only one or two sentences:

"In Moulmein, in Lower Burma, I was hated by large numbers of people—the only time in my life that I have been important enough for this to happen to me. I was sub-divisonal police inspector of the town." Then, later, it says: "I had already made up my mind that Imperialism was an evil thing, and that the sooner I chucked up my job and got out of it the better." A little further on it states: "All I knew was that I was stuck between my hatred of the Empire I served and my rage against the evil spirited little beasts which tried to make my job impossible. With one part of my mind I thought of the British Raj…"(read Orwell's full essay here.)

It is very good reading; I thoroughly enjoyed it, but I say that it is an example of the sort of thing which should not be said on the air at this stage, either here or anywhere else. I am not saying that this particular broadcast was typical, but it is one example which came to me; I do not think it was typical, but I do think that it should not have been made.

I am not blaming the B.B.C. for the failure to carry out the right broadcast propaganda programmes; but I am blaming the Government for their spineless approach to the deteriorating situation in the Far East, because, without a proper foreign policy, our propaganda can never be really effective; and who knows what our policy is in, for example, China, where we are wandering around asking them on what terms we shall recognise them.

The third question with which we have to concern ourselves is, why does the B.B.C. "project Britain" through its Far Eastern service, while Radio Malaya carries on a propaganda campaign mixed in with its ordinary programmes? Is Hong Kong doing propaganda, or is it not? Then, why should one Minister have one policy in the Far East, while another has a totally different policy? (Ceylon Broadcasting Volume 476: debated on Thursday 29 June 1950)

The proceeding between Major Beamish, a British Army officer and Conservative Member of Parliament for Lewes, and Mr Hobson, the Assistant Postmaster-General speaking for the BBC, is a powerful case of the influential power of George Orwell - both as a novelist and a BBC broadcaster. For the purposes of this site, George Orwell (or Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950) is a fascinating look into how the BBC saw and dealt with the Far East (a constructed regional name that then encompassed most of what is now South East Asia).

Eric Arthur Blair was born on 25 June 1903 in Motihari, Bengal Presidency (now Bihar), British India, into what he described as a "lower-upper-middle class" family. Blair's maternal grandmother lived at Moulmein, so he chose a posting in Burma, then still a province of British India. In October 1922 he sailed on board SS Herefordshire via the Suez Canal and Ceylon to join the Indian Imperial Police in Burma. A month later, he arrived at Rangoon and travelled to the police training school in Mandalay. He was appointed an Assistant District Superintendent (on probation) on 29 November 1922, (The India Office and Burma Office List: 1927. Harrison & Sons, Ltd. 1927. p. 514.)

In Burma, Blair acquired a reputation as an outsider. He spent much of his time alone, reading or pursuing non-pukka activities, such as attending the churches of the Karen ethnic group. A colleague, Roger Beadon, recalled (in a 1969 recording for the BBC) that Blair was fast to learn the language and that before he left Burma, "was able to speak fluently with Burmese priests in 'very high-flown Burmese'." (A Kind of Compulsion, 1903–36, p. 87)

After a series of illnesses, changes of mind and fighting in the Spanish War, Orwell obtained "war work" when he was taken on full-time by the BBC's Eastern Service. He supervised cultural broadcasts to India to counter propaganda from Nazi Germany designed to undermine imperial links. This was Orwell's first experience of the rigid conformity of life in an office, and it gave him an opportunity to create cultural programmes with contributions from T. S. Eliot, Dylan Thomas, E. M. Forster, Ahmed Ali, Mulk Raj Anand, and William Empson among others.

Eric Arthur Blair was born on 25 June 1903 in Motihari, Bengal Presidency (now Bihar), British India, into what he described as a "lower-upper-middle class" family. Blair's maternal grandmother lived at Moulmein, so he chose a posting in Burma, then still a province of British India. In October 1922 he sailed on board SS Herefordshire via the Suez Canal and Ceylon to join the Indian Imperial Police in Burma. A month later, he arrived at Rangoon and travelled to the police training school in Mandalay. He was appointed an Assistant District Superintendent (on probation) on 29 November 1922, (The India Office and Burma Office List: 1927. Harrison & Sons, Ltd. 1927. p. 514.)

In Burma, Blair acquired a reputation as an outsider. He spent much of his time alone, reading or pursuing non-pukka activities, such as attending the churches of the Karen ethnic group. A colleague, Roger Beadon, recalled (in a 1969 recording for the BBC) that Blair was fast to learn the language and that before he left Burma, "was able to speak fluently with Burmese priests in 'very high-flown Burmese'." (A Kind of Compulsion, 1903–36, p. 87)

After a series of illnesses, changes of mind and fighting in several wars, Orwell obtained "war work" when he was taken on full-time by the BBC's Eastern Service. He supervised cultural broadcasts to India to counter propaganda from Nazi Germany designed to undermine imperial links. This was Orwell's first experience of the rigid conformity of life in an office, and it gave him an opportunity to create cultural programmes with contributions from T. S. Eliot, Dylan Thomas, E. M. Forster, Ahmed Ali, Mulk Raj Anand, and William Empson among others.

The Macguffin of BBC Sound

For many years, an actual recorded George Orwell broacast has yet to be found. Perhaps the closest one can sidle up to listen to him is via this recording of Venu Chitale who began her career at the BBC in 1940 as secretary to author George Orwell. She later on became a Talks Producer in the Indian Section and became a prominent broadcaster on both the Eastern Service as well as the domestic UK Home Service.

This absence of Orwell's recorded voice seems implausible as many of the broadcasts were played on relay and would have had to be recorded if the time slots for the Eastern and Far Eastern Service could be synchronized with the GMT. The conundrum is so baffling that some shcolars have pointed out this memo as a possible reason:

Memo criticising Orwell's voice: Is George Orwell's voice suitable for broadcasting?

Written: 1943

Synopsis: JB Clark, the Controller of Overseas Services, is the author of this memo wondering whether Orwell should be kept on the air due to the unattractive nature of his voice. Clark feared not only that the talks might be compromised by Orwell's vocal delivery, but also that the BBC could be criticised for giving airtime to somebody with such an unsuitable way of speaking.

However, given the vast number of recordings at the British Library—only 40 percent of which is catalogued—and the even more extensive BBC Sound Archive in Perivale, there might still be a chance of discovering that elusive disc containing Orwell's voice.